Birding

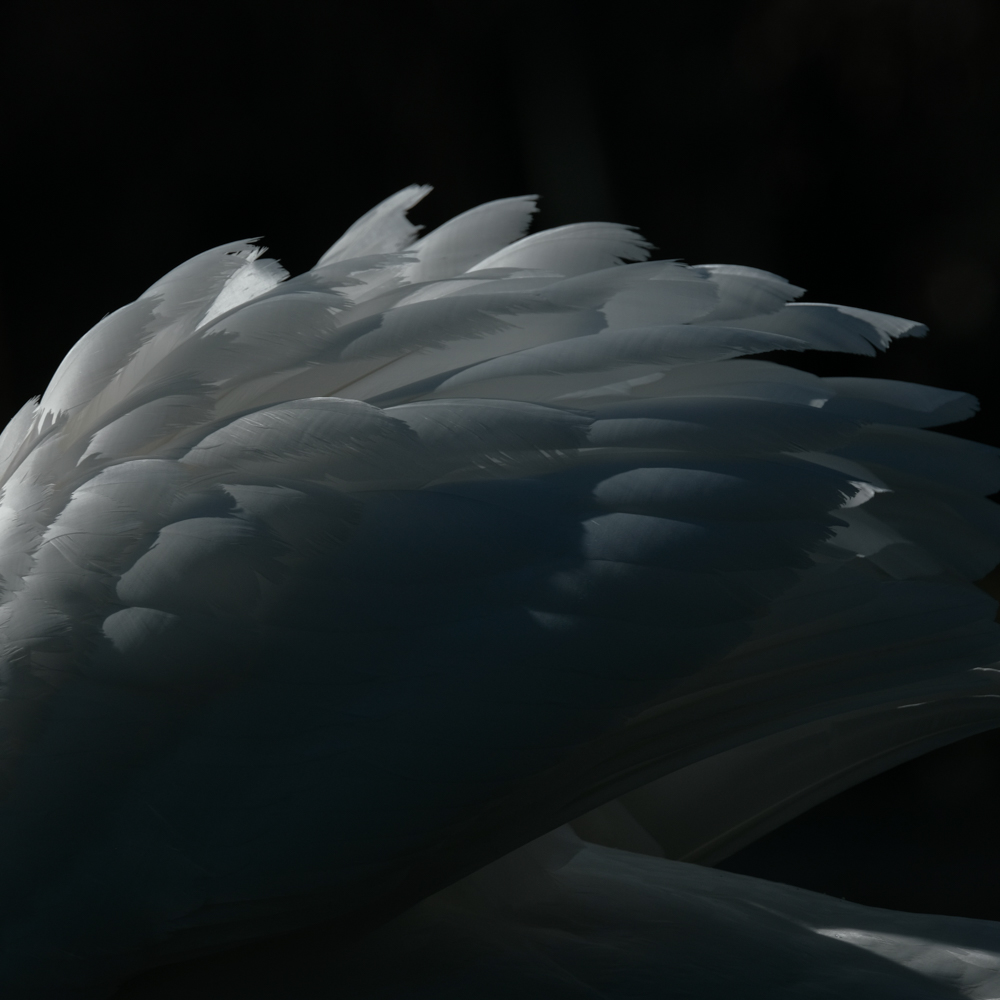

Sometimes, it feels like I am already experiencing symptoms of an aging body and mind: I am getting more conservative, my back often hurts, recovery from sports takes longer, and suddenly I appreciate trees. And flowers. And birds.

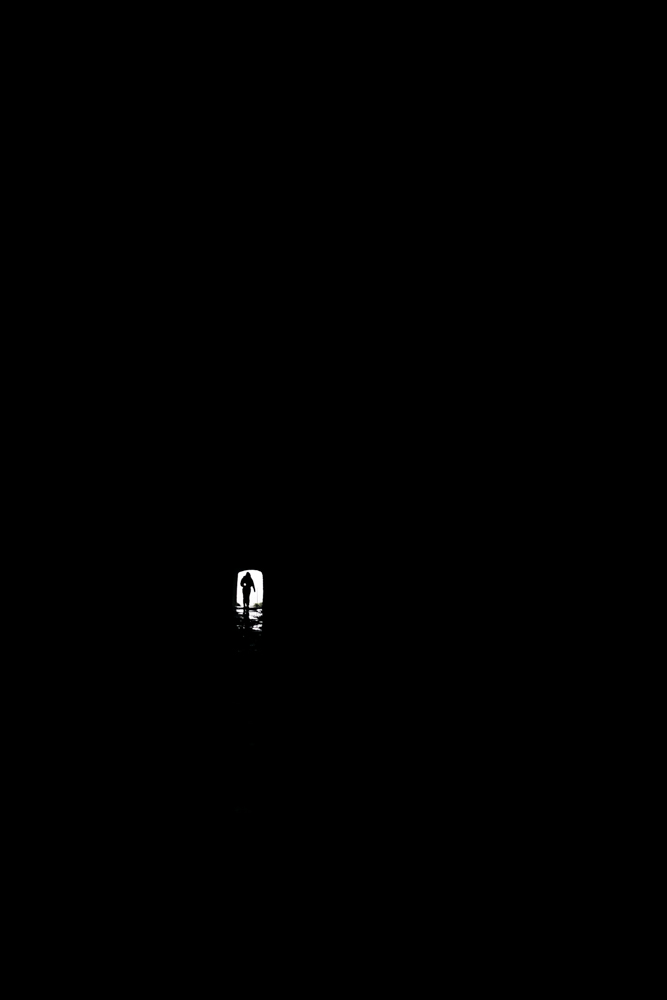

In my younger days, I was convinced that birdwatching is boring; but it has grown on me. Birds are adorable. From the smallest goldcrest to the great bustard (hopefully I’ll see one someday), every type of bird is so unique and fascinating and there is so much to learn: about their behaviour, calls, appearance, and migration patterns. Depending on the employed definition, there are between 10,000 and 20,000 bird species on earth. In Scotland we saw at least 63, many of which I have never seen before. I was a real treat to experience the puffins, razorbills, and guillemots at the coast. On our last day alone we spotted a spoonbill, a barnowl, sedge warblers, and a gannet, none of which I had ever seen before.

But again, the climate is changing everything: The spoonbill populations are slowly shifting north due to the increasing temperature. We got told that it was only the second time that an individual was spotted at the small lake where we parked over night. It is estimated that 15% of all species might go extinct soon (in evolutionary timescales) because they cannot cope with the rapid changes of the climate. Around our hometown some bird populations even increase, but the majority declines. Especially endangered are those that breed on farming grounds because of the streamlined agriculture occupying large amounts of space, often with monocultures. On the bright side: At least around here there are also increasing amounts of ‘Blühstreifen’, strips of wild herbs and flowers that are incorporated into the conventional agriculture and run along all the fields of wheat and corn. And if it doesn’t work out for the birds, my personal contingency plan is to just see all 10,000 species soon enough.