Dance of the Swans

11:25

Zuhause

suche ich die Heimat

umsonst.

11:26

Draußen

ist die Heimat

umsonst.

15:41

Wortgesuche

um den verlorenen Sinn

zu vergessen.

16:17

Aus Sehnsucht

und Verdruss

formen sich Träume.

Enjoying nature and photography.

11:25

Zuhause

suche ich die Heimat

umsonst.

11:26

Draußen

ist die Heimat

umsonst.

15:41

Wortgesuche

um den verlorenen Sinn

zu vergessen.

16:17

Aus Sehnsucht

und Verdruss

formen sich Träume.

Spring went as quickly as it came,

and summer knocks with heavy rain

on our door and window front,

but most things stayed the same, quite lame:

The wren berates the passing cats,

at evenings we watch the bats,

the nightingales still sing aloud,

and locals show quite proud

the whole island to every crowd.

The time of winter vegetables is over and suddenly there is a lot more than only cabbage: cucumber, green beans, salad, kohlrabi (why is this the correct English word?), and fennel. Especially on the island, things seem to grow fast. In accordance, April continued the temperature high of the first three months and brought us 30 degrees before my birthday. Just to plummet to zero afterwards. Thus, somehow here we are, still discussing e-fuels and heat pumps. So, instead of debating politics, we continued to learn a lot about birds. Most recent progress includes the effortless identification of the songs of the short-toed treecreeper, the willow warbler, and the Savi’s warbler – black birds and starlings are breeding in the garden, and the frogs intone their chants. I am ready for summer.

The plumage arranged

and each feather exchanged,

while yonder awaits

those who ponder and wait,

as wings are awaiting blue skies.

77 760 000 heart beats of a robin, 39 340 000 fallen leaves on the island dam, 9 072 000 heart beats for me, 246 000 migratory birds at lake constance, 17 300 people for democracy, 2398 lines of code, 830 kilometers on the bike, 462 hours of work, 91 sunrises, 35 bouldering sessions, and three full moons.

While we experienced the longest summer last year, from autumn to early spring felt like a single heartbeat. Is this a glimpse of the future?

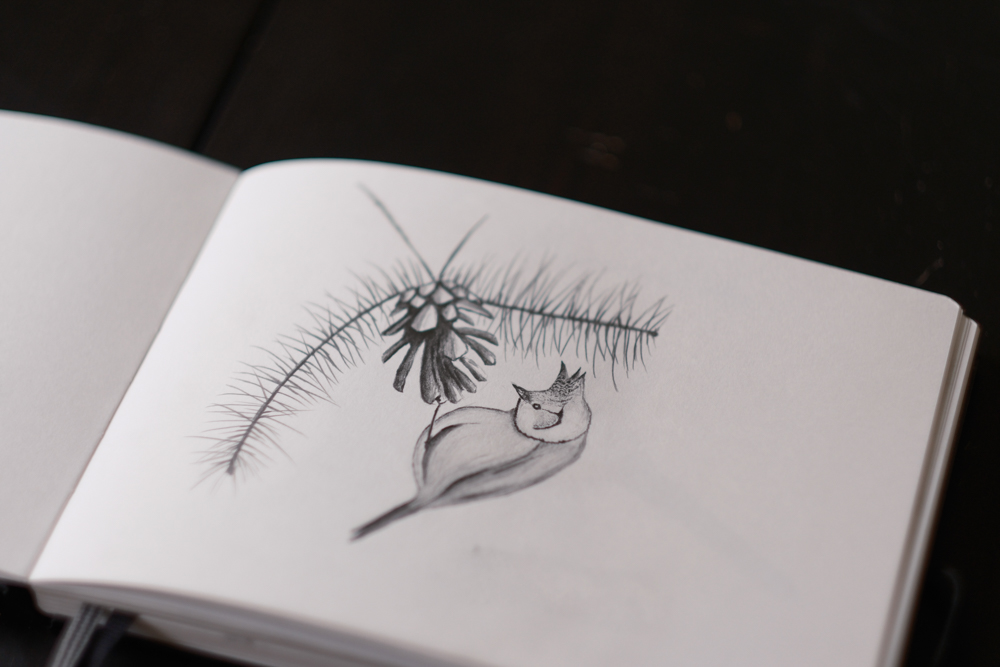

‘Lately, we have been photographing many birds – I even bought a used lens for wildlife, but I am still struggling to use it properly.’

This is how I started this blog post – more than three years ago. It should’ve been my second post ever, but for some reason I never finished it. Until now.

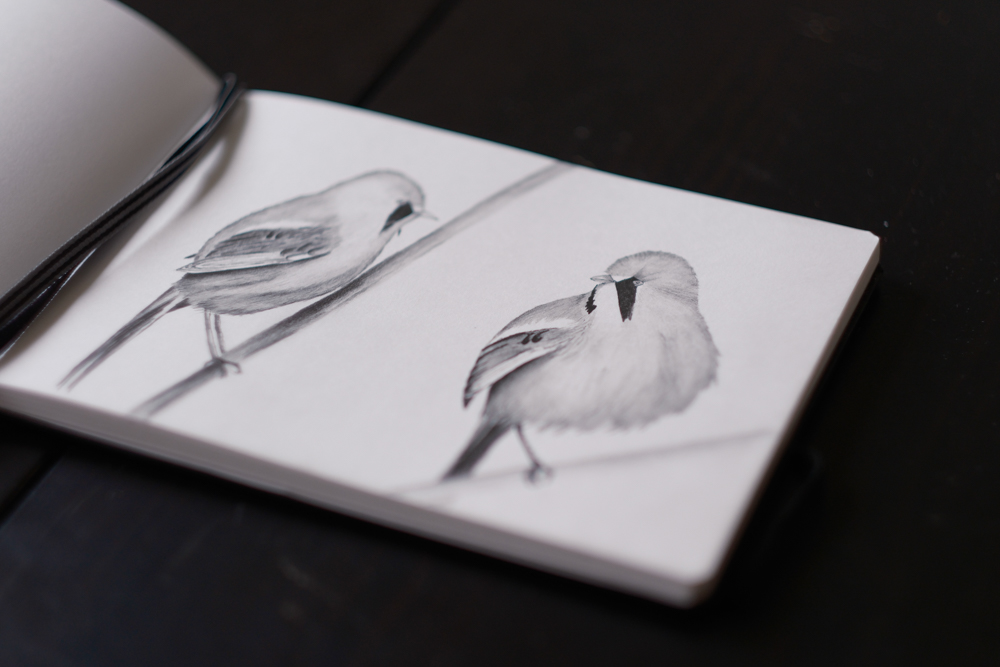

One of the most dominant groups of birds in our region are tits, grouped together into the taxonomic family of Paridae. Especially during winter time they are omnipresent and like to cause havoc at the feeding stations. Still, they are absolutely lovely: Little balls of fluff, chirping around non-stop, and always bouncing around between the branches faster than any camera can focus. In total the family comprises 63(!) species, scattered mostly across the northern hemisphere and some regions of Africa. Because of their noisy nature, North American representatives of the family are also referred to as chickadees.

In Europe alone, there are great tits (Kohlmeisen), eurasian blue tits (Blaumeisen), marsh tits (Sumpfmeisen), coal tits (Tannenmeisen), willow tits (Weidenmeisen), and crested tits (Haubenmeisen). And for each of them, there are often close relatives in other geographic regions. For example, eurasian blue tits belong to the genus of Cyanistes which they share with african blue tits (Northern Africa and Canary Islands) and azure tits (parts of Asia); especially the latter are beautiful, check them out.

For some species, the classification as a tit came rather late due to their unusual appearance and habits: For example, ground tits and sultan tits have very distinct visuals and characteristics and were only included after analyzing their genomes. And to this date the debate about their exact systematics is still ongoing.

I also just recently discovered that our favorites, the long-tailed tits (Schwanzmeisen), taxonomically don’t even belong to the family of Paridae – and neither do penduline tits (Beutelmeisen) nor bearded seedlings (Bartmeisen)! We saw the latter just last autumn for the first time, check it out here. Thus, despite their deceptive German names they do not share a common ancestry with other tits inside the family of Paridae. Furthermore, penduline tits are sadly extinct in our region anyways and the last sighting of their nest in our region is already more than 7 years ago).

For more information I suggest you check out birdsoftheworld.org.

A brief break

to take a breath,

a brake in life

to take a step

back, two steps

onwards,

as soon awaits the biting cold –

so, take your skates,

roll out and trust:

yourself,

and the ice shelf,

through faded sceneries

where bare trees house

jaded starlings

left alone

within the snow,

I am still watching, though,

behind the door,

while the world awaits outside.

It’s a calm morning. Fog encloses the island and mutes the distant cars. The sailing ships are all lined up neatly, one after another, swaying gently on the waves. Next to the ships, there are the bollards. They are lined up neatly as well, ready to welcome any new arrivers. And then there is Gustav, the black-headed gull.

Gustav occupies one of the bollards, but he isn’t the only one. Next to him are all his mates – also, of course, lined up neatly: One bollard, one gull. As it should be. Gustav is satisfied. That’s how he likes his mornings. That’s how he likes his bollards. But then, a new arriver appears. And Gustav knows that there will be turmoil.

Before he can prepare himself, the attack from high above is in full swing. A quick stroke with the wing, a brief chop with the beak, and suddenly his neighbor is tumbling to the ground. Before the attacker can seize his earned place, two distant acquaintances of Gustav are already brawling for the now empty bollard. Claws get sharpened, feathers are plucked, with every passing second a new contender joins in. A whole squadron of coots start to cheer on the warfare. The snide remarks of Carl the cormorant echo across the water. Herbert the heron escapes quietly. Gustav tries to be as inconspicuous as possible.

The calm morning has turned to chaos – as every day.

The number of black-headed gulls around the lake has dropped profoundly over the last 30-40 years, presumably by more than 70%. It’s ‘just’ a local decline and most gulls seem to relocate to other areas. Apparently one reason is the increase in water clarity that comes with a reduced offer of food. While the gulls have been seen as a real nuisance in the past, they are now missed by many.

When I started photographing birds a few years ago I couldn’t identify more than five species at maximum. Already the yellow feathers of a goldfinch (Stieglitz) would make me wonder what kind of special species I am witnessing. It then also took me several months to realize that it’s the same bird as a Distelfink.

Back then I also wasn’t aware of the immense diversity of birds around the globe: Most of our local species in Germany share their families with many other species that often inhabit the different continents. But even within Europe there is a large diversity: the Iberian peninsula alone hosts many endemic species and, thus, on our trip during the past summer we had the pleasure to engage with this large new world of birds. This is a brief overview.

Our first special encounter was with vultures, birds that impressed me so profoundly I already wrote about them earlier.

In the Pyrenees we observed a wryneck couple and learned their unambiguous calls. After listening for the whole morning I was finally able to spot one of them as well; they surely are the most camouflaged birds I have seen so far. We also saw several dippers in the mountain streams between France and Spain – and even spotted a nest in the Gorges de la Carança.

Then, the delta of the Ebro river greeted us with all its water birds: Flamingos, cattle egrets, little egrets, glossy ibises, black-winged stilts, all the gulls, and sandpipers – just to name a few.

Redstarts visited us on most campsites and bee-eaters decorated the power lines. Rock buntings and corn buntings lined the hiking trails. However, among my favorites were the many swallows, swifts and martins. They were everywhere. And they were many. Something I am truly missing here back home in Germany.

And as soon as the night time start there are the owls. Every single night we would hear another one. Often scops owls, but also little owls and tawny owls. Every night – simply beautiful.

Coming into the Southern regions, we watched hoopoes digging for ants, Iberian magpies grabbing tourists’ food, spotless starlings snacking from trees, Sardinian warblers sleeping in the sun, and black-headed weavers weaving their nests. The list of birds seems endless; we counted at least 110 species, including many we never saw before.

Who doesn’t love swallows? They are as fast as the wind, always chatty, and super cute. The Common House Martin we have here in Europe is only one of four species within the genus of Delichon, whereas the other three species are distributed around Africa and Asia. They love pastures and farmland, especially near water, and build their distinctive nest out of mud and clay beneath overhanging rock formations or buildings.

We had the pleasure to be surrounded by hundreds of them while standing on the dam of Embalse de los Bermejales. They were zipping all around us, seemingly not concerned with or interested in anything else than the delight of their flight. And for a moment, it felt like we were among them – a moment I will gladly remember for years to come.