A Large Family of Small Birds

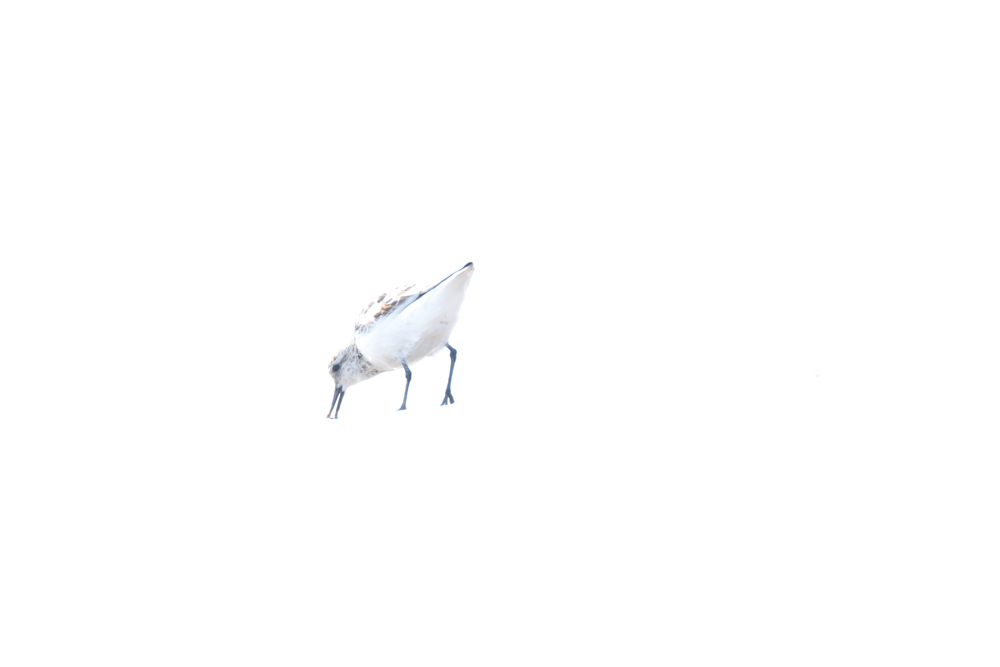

‘Lately, we have been photographing many birds – I even bought a used lens for wildlife, but I am still struggling to use it properly.’

This is how I started this blog post – more than three years ago. It should’ve been my second post ever, but for some reason I never finished it. Until now.

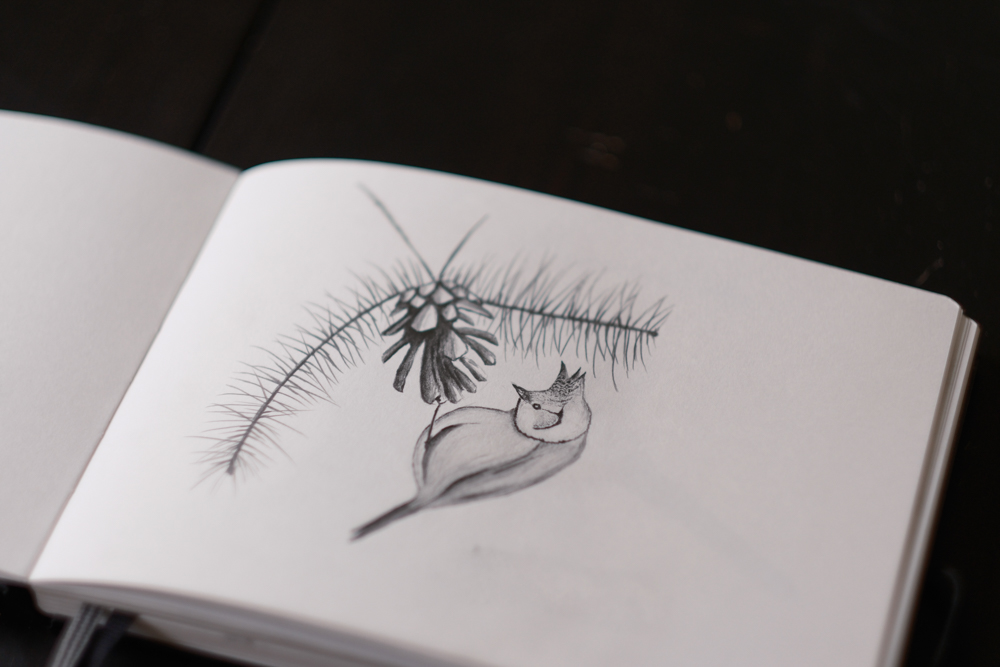

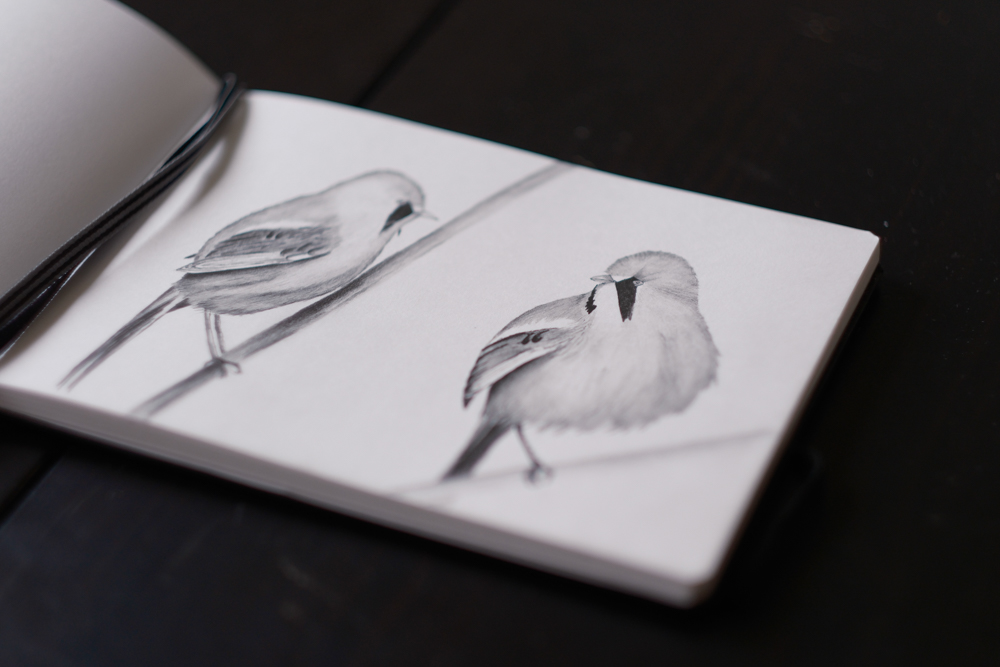

One of the most dominant groups of birds in our region are tits, grouped together into the taxonomic family of Paridae. Especially during winter time they are omnipresent and like to cause havoc at the feeding stations. Still, they are absolutely lovely: Little balls of fluff, chirping around non-stop, and always bouncing around between the branches faster than any camera can focus. In total the family comprises 63(!) species, scattered mostly across the northern hemisphere and some regions of Africa. Because of their noisy nature, North American representatives of the family are also referred to as chickadees.

In Europe alone, there are great tits (Kohlmeisen), eurasian blue tits (Blaumeisen), marsh tits (Sumpfmeisen), coal tits (Tannenmeisen), willow tits (Weidenmeisen), and crested tits (Haubenmeisen). And for each of them, there are often close relatives in other geographic regions. For example, eurasian blue tits belong to the genus of Cyanistes which they share with african blue tits (Northern Africa and Canary Islands) and azure tits (parts of Asia); especially the latter are beautiful, check them out.

For some species, the classification as a tit came rather late due to their unusual appearance and habits: For example, ground tits and sultan tits have very distinct visuals and characteristics and were only included after analyzing their genomes. And to this date the debate about their exact systematics is still ongoing.

I also just recently discovered that our favorites, the long-tailed tits (Schwanzmeisen), taxonomically don’t even belong to the family of Paridae – and neither do penduline tits (Beutelmeisen) nor bearded seedlings (Bartmeisen)! We saw the latter just last autumn for the first time, check it out here. Thus, despite their deceptive German names they do not share a common ancestry with other tits inside the family of Paridae. Furthermore, penduline tits are sadly extinct in our region anyways and the last sighting of their nest in our region is already more than 7 years ago).

For more information I suggest you check out birdsoftheworld.org.